|

| Re-enactor from First Bulgarian State (theapricity.com) |

First Contact

The Coming of the Bulgars

The Roman campaign against the invading Bulgar tribes ranks as one of the most important in history because the Roman defeat resulted in the creation of a new Bulgarian Empire. Over the next 675 years the Bulgarians would become either allies or more often deadly enemies of Constantinople.

The Bulgars were a semi-nomadic Turkic people who flourished in the Pontic Steppe and the Volga basin in the 7th century AD.

The early Bulgars may have been present in the Pontic Steppe from the 2nd century, identified with the Bulensii in certain Latin versions of Ptolemy's Geography, shown as occupying the territory along the northwest coast of Black Sea east of Axiacus River (Southern Bug).

In the early 4th century, the Bulgars would have been caught up in the Hunnic migrations, moving to the fertile lands along the lower valleys of the rivers Donets and Don and the Azov seashore. Bulgars took part in the Hunnic raids on Central and Western Europe between 377 and 453.

At the end of the 5th century (probably in the years 480, 486, and 488) they fought against the Ostrogoths as allies of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno. From 493 they carried out frequent attacks on the western territories of the Byzantine Empire. Later raids were carried out at the end of the 5th century and the beginning of the 6th century.

Slowly the Bulgar peoples moved from what is modern Ukraine down into the Balkans and increasing came into contact with Roman troops at the Danube River frontier.

|

| Roman Emperor Constantine IV Emperor Constantine IV and his court. He organized the military and city of Constantinople for a siege of five years while fighting wars on multiple fronts over three continents (Africa, Europe and Asia). After the defeat of the Arabs the Emperor personally led an army against the invading Bulgars. . (Mosaic in basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe Ravenna, Italy.) |

Of Arabs and Bulgars

The Heraclian dynasty Emperors of Rome faced the near extinction of the Empire from multiple enemies on multiple fronts. Constantine IV (668 – 685) was simultaneously fighting wars in Italy, Africa, the Balkans and Anatolia.

His greatest challenge was withstanding the massive Arab Siege of Constantinople that lasted from 674-678.

The city survived, and finally in 678 the Arabs were forced to raise the siege. The Arabs withdrew and were almost simultaneously defeated on land and sea in Lycia in Anatolia. This unexpected reverse forced the Arabs to seek a truce with Constantine. The terms of the concluded truce required them to evacuate the islands they had seized in the Aegean, and to pay an annual tribute to the Emperor consisting of fifty slaves, fifty horses, and 3,000 pounds of gold.

At the same time a Roman army in the Exarchate of Carthage North Africa was battling against invading Muslim Arabs.

With the Arab forces totally defeated at Constantinople and Lycia the Emperor could turn his attentions to the invading Bulgars.

|

| The Bulgar Khan Asparuh Founder of the Bulgarian Empire |

For centuries Roman Balkans had been either under attack or overrun by and endless stream of Asian tribes. Now it was the turn of the Bulgars.

The Khan Asparuh parted ways with the tribes to the north in order to seek a secure home on Roman Balkan territory. He was followed by 30,000 to 50,000 Bulgars.

He reached the Danube while the Byzantine capital Constantinople was besieged by Muawiyah I, Caliph of the Arabs. He and his people settled in the Danube delta, probably on the now disappeared Peuce Island.

After the Arab siege of Constantinople ended, Constantine IV gathered available troops and marched against the Bulgars and their Slav allies in 680. His attack forced his opponents to seek shelter in a fortified encampment.

Again the Romans faced another pagan invasion that threatened their security.

|

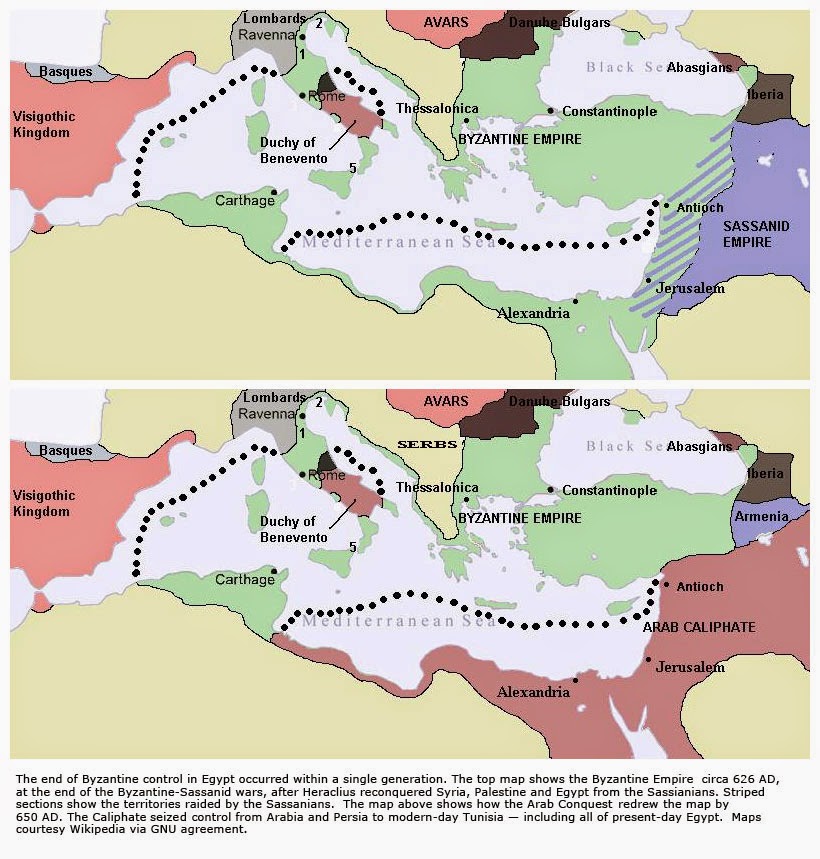

| Roman Empire military districts and force deployment in 668AD. The Empire had to defend North Africa, Italy the Balkans and Asia Minor. Click graphic to enlarge. |

Opposing Forces

The early Bulgars were a warlike people and war was part of their everyday life, with every adult Bulgar obliged to fight. The early Bulgars were exclusively horsemen: in their culture, the horse was considered a sacred animal and received special care.

The permanent army consisted of the khan's guard of select warriors, while the campaign army consisted practically of the entire nation, assembled by clans. In the field, the army was divided into right and left wings.

During the first decades after the foundation of the country, the army consisted of a Bulgar cavalry and a Slavic infantry. The core of the Bulgarian army was the heavy cavalry, which consisted of 12,000–30,000 heavily armed riders.

The Bulgars were well versed in the use of stratagems. They often held a strong cavalry unit in reserve, which would attack the enemy at an opportune moment. They also sometimes concentrated their free horses behind their battle formation to avoid surprise attacks from the rear.

|

| Eastern Roman Cavalry |

The army had iron discipline, with the officers vigorously checking if everything was ready before a battle. For a horse that was undernourished or not properly taken care of, the punishment was death. The soldiers were under threat of a death penalty when having a loose bow-string or an unmaintained sword; or even if riding a war horse in peacetime

The infantry of the newly formed state was composed mainly of Slavs, who were generally lightly armed soldiers, although their chieftains usually had small cavalry retinues.

The Slavic footmen were equipped with swords, spears, bows and wooden or leather shields. However, they were less disciplined and less effective than the Bulgar cavalry.

The Romans A direct descendant of the Roman army, the Byzantine army maintained a similar level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization. Over time the cavalry arm became more prominent as the legion system disappeared in the early 7th century.

The official language of the army for centuries continued to be Latin but this would eventually give way to Greek as in the rest of the Empire, though Latin military terminology would still be used throughout its history.

Tactics, organization and equipment had been largely modified to deal with the Persians. The Romans adopted elaborate defensive armor from Persia, coats of mail, cuirasses, casques and greaves of steel for tagma of elite heavy cavalrymen called cataphracts, who were armed with bow and arrows as well as sword and lance.

Large numbers of light infantry were equipped with the bow, to support the heavy infantry known as scutarii (shield men) or skutatoi. These wore a steel helmet and a coat of mail, and carried a spear, axe and dagger. They generally held the center of a Roman line of battle. Infantry armed with javelins were used for operations in mountain regions.

| The Battle of Ongal was east of Preslavets in the Danube River Delta. Red arrows show the Bulgar attacks to the south and the blue arrows the Byzantine land and sea movement to the Danube. |

The Battle of Ongal

The Kahn Asparukh had marched westward and settled with his folk in the Ongal area to the north of the Danube. From there he launched attacks against the Byzantine fortresses to the south. During that time Byzantium was at war with the Arabs who were besieging the capital Constantinople.

In 680, after the defeat of the Arabs, Constantine IV led a combined land and sea operation against the invaders and besieged their fortified camp in the Danube River Delta.

As usual little information is available on this all important campaign that resulted in the creation of the Bulgarian Empire.

Numbers of the troops involved are basically made up. One historian claims that Constantine marched north with 85,000 troops to face 40,000 Bulgars.

The number of Romans is absurd. The Byzantine historian Treadgold says the entire strength of the Roman Army at this point was 109,000 men under arms. The Byzantines never fielded forces this large in one place.

|

| Bulgar Warrior (worldhistoria.com) |

If you look at the force deployment chart above the Romans had some 40,000 troops stationed in the general Constantinople area and another 20,000 in the Theme of Thrace.

With the Emperor at the head of the army we can assume a larger than normal force was gathered. An army of perhaps 30,000 or more might be reasonable.

If 30,000 set out on campaign several thousand would never have made it to the battlefield. They would have been detached from the main army to protect supply lines back to Constantinople, occupy fortified points in the rear or to protect communications to the Byzantine navy off the coast.

The Bulgarians moved into Roman territory with 30,000 to 50,000 people including women and children. The male fighting force would be much smaller at perhaps 15,000.

The Bulgarian leader made an alliance with the Seven Slavic tribes for mutual protection against Byzantine attacks and formed a federation. So Slavic allies could have added to that total, but no information is available.

A Roman fleet sailed up the coast along side of the Emperor's army. The Bulgars did not have a navy to fight so we can assume that the ships transported supplies and perhaps reinforcements. There is no record of the navy participating in the battle in a meaningful way.

The Bulgars knew the Romans were coming for them. They built wooden ramparts in a swampy area near the Peuce Island in the Danube River Delta.

Emperor Constantine was over confident after his defeat of the Arabs. He sent his forces to attack the Bulgars on ground of their choosing, not his choosing.

The marshes and river delta would have prevented larger numbers of Romans from gathering in one location in defense or attack. The Byzantines were forced to attack from different places and in smaller groups which reduced the strength of their attack. With sudden strikes from the ramparts, the well-organized defense eventually forced the Byzantines to retreat, and the retreat developed into a stampede.

The Bulgar cavalry came out and charged the enemy who retreated chaotically. Most of the Byzantine soldiers were killed.

According to popular belief, the emperor had leg pain and went to Nessebar down the coast to seek treatment. The troops thought that he fled the battlefield and in turn began fleeing. When the Bulgars realized what was happening, they attacked and defeated their discouraged enemy. Accounts say that virtually the entire Roman army was destroyed.

Historical Speculation

Again, there is maddeningly little hard information for historians. But the "official" account of the battle, such as it is, does not ring true.

There should not have been all that many Buglar troops inside a slapped together wooden swap fort. Sure the Bulgars may have made a few ferocious attacks from the fort at the Byzantines. But the idea that the limited forces inside the fort would destroy a larger attacking Roman army is not believable.

What is more likely is substantial units of Bulgar cavalry, infantry and Slavic allies were operating outside the fort. The fort acted as bait to draw the Romans into battle. The wet delta river system would have made a Roman attack much harder and also split up their forces on to different islands and riverbanks so they were unable to support each other.

| Emperor Constantine IV |

The Bulgars may have been attacking Roman regiments isolated from each other by the delta. They may also have been working their way around to attack the flanks and/or the rear of the main Roman army working on the fort.

The Emperor leaves. The story is the Emperor suddenly decided in the middle of a campaign that he had "leg pain" and needed treatment far away from the battlefield.

This is pure press release political bull if you ask me.

More likely is that Constantine's generals came to him with reports that a number of his units out in the delta were being overrun by Bulgarian forces and that his army was in danger of being flanked or surrounded.

Political, not military considerations, would have caused the relocation of the head-of-state to prevent his capture or death by an invading enemy.

The Emperor would not have left by himself. He would have taken with him his staff and a large bodyguard of troops for protection. Troops that would have been vital to strengthen Roman defenses.

It is reasonable to assume that with the battle already going badly the flight of the Emperor added to the panic of the troops causing a total collapse and the Bulgarian victory.

| Battle of Ongal Screen shots of the battle in a Bulgarian language YouTube video. The movie clip is pretty good showing the wooden defensive walls and the Byzantine attackers. The wet, delta conditions were not really addresses. Link Battle of Ongal |

Aftermath

After the victory, the Bulgars advanced south and seized the lands to the north of Stara Planina. In 681 they invaded Thrace defeating the Byzantines again. Constantine IV found himself in a dead-lock and asked for peace. With the treaty of 681 the Byzantines recognized the creation of the new Bulgarian state and were obliged to pay annual tribute to the Bulgarian rulers.

The Romans were greatly humiliated. The empire had recently defeated the Sassanid Persians and the Ummayad Arabs. Now they in turn had been decisively beaten by an invading tribe from Asia.

This battle was a significant moment in European history, as it led to the creation of a powerful state, which was to become a European superpower in the 9th and 10th century along with the Byzantine and Frankish Empires. It became a cultural and spiritual centre of Slavic Europe through most of the Middle Ages.

|

| The foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire. The army of Asparukh is in red. The army of Constantine IV is in blue. |

|

| The new Bulgarian Empire after the Battle of Ongal. |

(Medieval Bulgarian Army) (militaryhistoryonline) (theapricity.com)

(Bulgars) (Asparuh) (Ongal)

.jpg)